Chapter 3 – The Utilities. The story of Luton’s Gas, Railway, Water and Electricity Services.

There can be little doubt that the foresight of Luton’s businessmen, whose willingness to finance and support the town’s public utility services, indirectly brought about the expansion that changed Luton from a country village into a large industrial town in the 19th and 20th centuries. The utilities, namely The Luton Gas Company, The Luton Water Company, The Luton Electricity Company and various railway companies, all of which were successful in their own right, were used by the New Industries Committee as a lure to attract companies and especially new industries to Luton, by the promise of cheap land and favourable prices of services offered by the established local utilities.

THE LUTON GAS COMPANY (1833-1949)

Gas produced from coal was first used as an illuminant by William Murdock, an engineer, towards the end of the 18th century in Birmingham. By 1810, businessmen in larger cities and towns such as London, York and Oxford had already formed companies and started erecting factories for producing inflammable gas from coal.

Until the 1830s, street-lighting in Luton had been a haphazard affair, the falling of darkness bringing about a virtual curfew, while the only options available to light homes or work places being tallow dips, oil lamps or candles. A factor holding Luton back in proceeding with gas lighting as quickly as other towns was the difficulty of coal supply. Not being on a navigable river or canal meant that coal deliveries had to be made by horse and wagon. After a long study that showed that the coal supply and transport was feasible, several Luton businessmen got together and formed a public company with the intention of “improving the illumination of the town by means of coal gas”.

In 1833, the first General meeting was held at the George Hotel where a chairman, secretary and directors were elected and a share capital of £2500 approved. All that was required was a site, quotations for the “gas-making” equipment, the laying of mains and pipes and of course the customers. Estimates to make sure of the economic viability were based on the need for coal gas to be piped to approximately fifty street lamps owned by the Borough, lit and maintained by their own lamplighters, plus one hundred and fifty piped installations in homes, shops and workshops. The best vacant site available for the factory buildings was in Dunstable Lane (today’s Dunstable Road) and belonged to a Mr Burr, a local brewer, who, after bargaining, sold the plot to the Gas Company for fifty pounds.

It must be borne in mind that the original gas works was only a pilot plant, with one retort for heating the coal and a small gas holder to contain the product. When gas production commenced, the first consumers were charged 14 shillings (70 pence) per thousand cubic feet, but as the company flourished, with better equipment and more customers, the price dropped to two shillings and tuppence (11 pence) per thousand cubic feet.

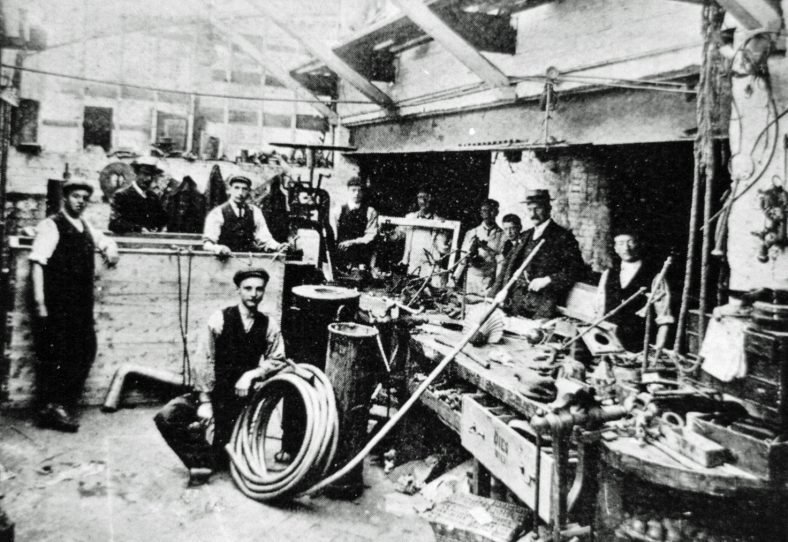

The interior of T. Wood & Sons workshop in Chapel Street in the early 1900s. Gas pipes made of lead and used for domestic supplies were cut to size and roughly shaped then fitted in houses and made gas-tight by a melt and wipe process known as lead burning. Lead poisoning was the occupational illness common to fitters who carried out this work.

The confidence of shareholders must have been shaken on Friday, 27th September, 1834, however, for it was to have been the night that the street lamps were to be lit in the main street for the first time. Unfortunately the cables used for supporting the gas holder as it rose and fell when being filled or emptied, jumped over the pulley-wheels on the support frame and jammed so tightly so that the gas could not be fed to the gas mains. There must have been many disappointed Lutonians who went home muttering dark thoughts, to even darker houses that night. However, by Thursday, 10th October, the problem had been resolved and the directors of The Luton Gas Company were able to stand and drink a toast to celebrate, “the lighting of the town”, at the George Hotel, in a room lit by gas burners!

Manufacturing the gas proved to be a hot, steamy and smelly process, gas coal having to be heated to a very high temperature in a retort to drive the gas off. After the gas had been distilled from the coal and washed in a scrubbing chamber, the residue left in the retort was quenched with water to cool it quickly, the by-products left being coke and tar. The area of the works where these processes were carried out was constantly shrouded in water and gaseous vapours which, because of the humid conditions led to mothers bringing children with whooping-cough and other bronchial ailments to promenade around the factory perimeter walls to get relief from the coughing.

The Luton Gas Company factory and offices in1879. Seeing this collection of industrial buildings edging a rural Dunstable Road, it is difficult to imagine how the technical complexity of the gas industry became established before the avalanche of twentieth century invention.

By 1890,the demand for gas by consumers was such that a second gas-holder, of 324,000 cubic feet capacity, was built. Gas proved to be such a popular fuel that two further holders were erected; one in 1900, capable of holding 678,000 cubic feet and another in 1910, the fourth and largest on the site, which held 1,100,000 cubic feet. Lutonians certainly warmed to the use of gas and as time passed it was not only the gas-holder capacity that increased. In the 1870s, an office block and additional buildings to house new retorts and purifying plant were erected, sidings connected to the newly laid nearby railway line and a weighbridge installed for weighing the coal and coke.

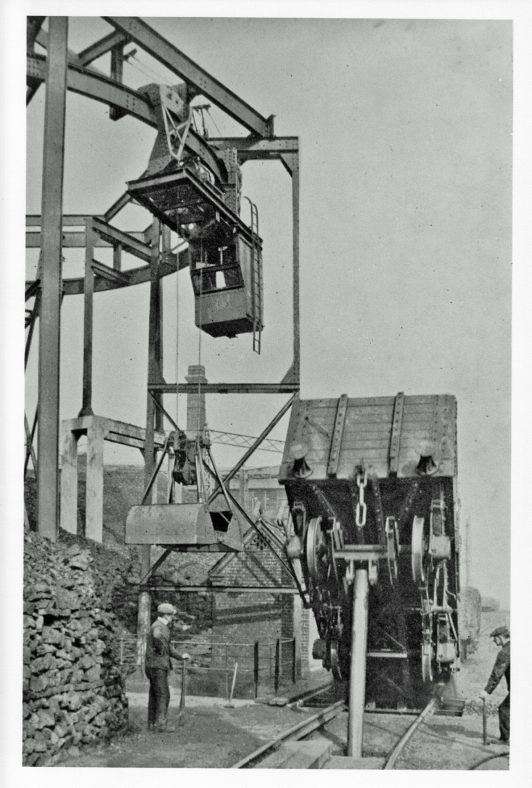

On the Gas Works sidings, 12 ton railway trucks were up-ended by means of a hydraulic ram and the cargo of coal unloaded into a storage pit below the rails. When retorts were ready for loading, coal was lifted from the pit with the grab and moved on the overhead monorail.

By the early 1900s all but the meanest of houses in Luton were connected to the gas supply. The average two bed-roomed terraced houses of the time were usually fitted with single fishtail burners in each of the bedrooms while in the downstairs rooms, two burners were usually mounted, one on either side of the fireplace and another in the centre of the ceiling. The kitchen or scullery generally had to make do with but a single burner near the copper or the sink. Although the fishtail burner was a great step forward compared with candles or oil lamps, the light they emitted was yellowy-blue in colour and a strain on the eyes to read by. An enormous improvement came about with the invention of the Welsbach incandescent gas-mantle, a small delicately shaped mesh dome made of fine fireclay, which when covering a flame produced a brilliant white light.

In 1907 advertisements extolling the virtues of the newly introduced incandescent lighting were appearing in most trade journals and local newspapers. Notice how cheap it was to rent a “cooking stove” at that time, from 25p to 60p per annum.

With the coming of the gas mantle, improved intensity of lighting in Luton streets and houses changed the after-dark outlook of the population and in so doing altered the life-style of most of them. The introduction of this simple notion meant that townsfolk could enjoy the extra after-dark time made available for family activities; churches were able to open for evening services all the year round and utilise the buildings for social and educational purposes through-out the week; owners of shops, workshops and offices were delighted with the extended productive working hours; public halls were able to provide accommodation for evening meetings and entertainments; while the improved street lighting made for safer streets.

The introduction of the incandescent lamp did not mark the end of the improvements introduced by the Luton Gas Company for they were an innovative company, being pioneers in materials and mechanical handling. The Company could see that the Dunstable Road site had insufficient room for further expansion of gas production and looking to the future, bought a second site in Dallow Road. In 1929, new showrooms were built in George Street and Dunstable Road to display and sell the continually growing range of gas-using appliances on the market and gas fires, geysers for heating bathwater and refrigerators were all the rage.

An interior view of the new George Street Showrooms, decorated in baronial style, in 1929. The range of gas lamps, fires and cooker may look archaic and outmoded by today’s standards, but they were considered the height of fashion at the time.

In the late 1930s, the George Street showroom was rebuilt in modern style with larger display areas and windows onto the main street, accounts offices and even a small theatre where films and cookery demonstrations could be held.

In the late 1930s the reconstructed Gas Showroom building was looked upon as the best designed structure in George Street. When completed, the public were particularly impressed with the Art Deco style sculptured panel of a figure looking out over the main street. For some time, Luton Gas Company shared the occupancy with the Inland Revenue Collector of Taxes and the Mayfair Hairdressing Salon.

Behind the showrooms in Francis Street the company’s transport garages were built which housed a fleet of corporate lorries, vans and cars. With further expansion, part of the Dallow Road site was used for maintenance of the vehicle fleet and general storage of gas fittings and pipework. Because of the vast network of mains and pipes under Luton’s streets, the pipe connections in customers houses and the large numbers of appliances both domestic and commercial, the Company built up an organisation of office personnel, workshop staff and installation fitters to keep pace with the rising demand.

The Gas Company’s transport and liveried drivers on parade in Francis Street.

During the second World War when domestic coal was hard to come by, the coal merchants would help eke out the allocation with the offer of a small quantity of coke from the gas works. Thus using a by-product, which was at that time almost as precious as gold!

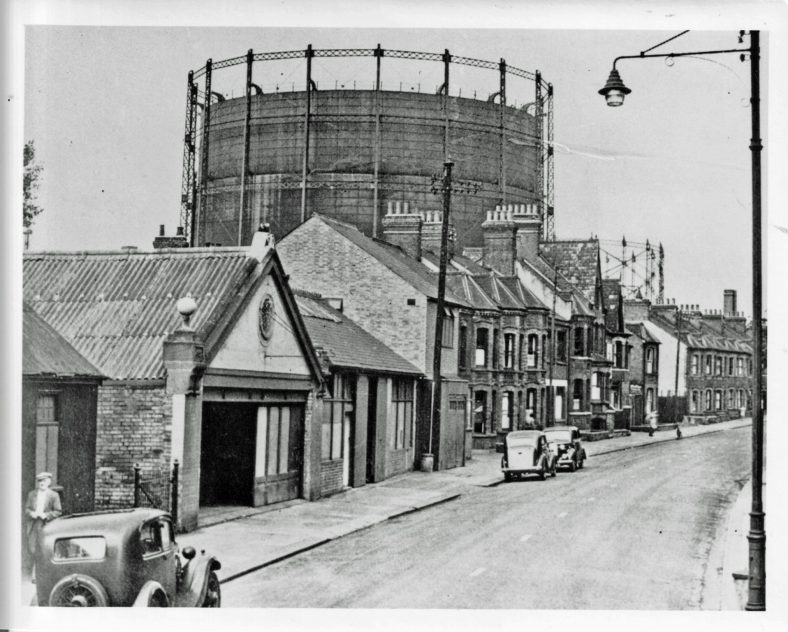

A view of Crawley Road showing how the housing was dwarfed by the size of an inflated gasholder. It was quite easy to see the effect that gas usage in cold weather or cooking the Sunday lunch had on the height of the enormous storage containers as they inflated or deflated in their supporting frames.

After the General Election following the second World War, the newly elected Labour Government passed legislation to nationalise several privately owned companies and bring them under State Control. As a result The Luton Gas Company, that had served Luton for over 110 years, was taken over on 1st May 1949 by the newly formed Eastern Gas Board, part of British Gas.

THE RAILWAY COMPANIES.

The opening of the Stockton and Darlington Railway in 1835 showed that travel by rail was a feasible proposition with enormous potential for improving transport and travel. Steam pioneers soon began to discuss ways of introducing a nationwide railway network but were often met with objections and opposition to their schemes. The father and son partnership of George and Robert Stephenson, engineers of “The Rocket” fame, were particularly anxious to promote a railway that would run from London to Manchester with Luton being one of the stations on the way.

In May,1844, The George Hotel hosted a meeting to discuss the scheme which was attended by the two Stephensons and several influential business men of the town. The majority were in favour of the Stephenson’s plans but because it involved trains being routed across a stretch of common land called the Great Moor, tempers ran so high that George and Robert Stephenson refused to talk further and left the meeting. George Stephenson’s parting shot became a Luton legend. “Luton will not have a direct railway line to London as long as I live” he ranted. It was an angry and prophetic look into the future that came true, for both father and son died before either of the railways giving direct access to London were completed.

The Moor was the controversial piece of common land over which the Stephensons wanted to run their first scheme for the London to Manchester Railway. It was not until both father and son had died that a similar plan was adopted allowing the railway to cross the common.

After the debacle of the meeting with the Stephensons, talks continued and mostly favoured a railway joining Luton and Dunstable, with the possibility of joining the London to Birmingham railway at Leighton Buzzard. Once again there were objectors, this time complaining of the extra time and distance that would be involved going to London via Leighton Buzzard. However, in 1855 an Act of Parliament was passed authorising the building of the Luton, Dunstable and Welwyn Railway and the joining of the two end stations, Welwyn and Dunstable, to the Hatfield and Leighton Buzzard lines respectively.

Lutonians knew that although regarded as a branch line it would at least give the route to London that they had been craving. On 25th October, 1855, the” turning of the first sod” marked the start of construction for the new railway. It was a gala day in Luton, despite the heavy rain, with a procession, bands, cheering crowds and a Civic Dinner at the Town Hall. However, would-be passengers had to live on their euphoria until the Luton to Dunstable portion of the line was completed three years later in May,1858.

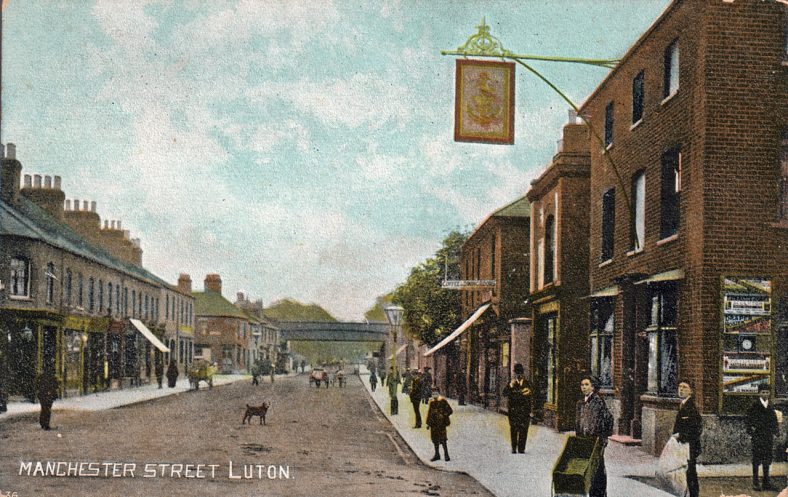

In the distance can be seen the first of the two railway bridges to span the New Bedford Road, carrying the Luton-Leighton Buzzard line, the first of the railways to pass through Luton. On the right is the Crown and Anchor public house. Everyone stops to watch the photographer, even the dog! Perhaps they realise he doesn’t know its really New Bedford Road.

A further two years were to pass before the Luton to Hatfield section was completed, enabling London to be reached without the necessity of changing trains. In 1860, Lutonians enjoyed the pleasure of making day return trips to London. For them the world had suddenly become a smaller place!

The London to Manchester Railway, originally proposed by George Stephenson, was beset with problems and arguments from the outset. The squabbles between investors and bankers, the route planning, the purchase of land, the death of both George (1848) and Robert (1859) Stephenson, the design of the infra-structure, getting Parliament to sanction the scheme, the placing of civil engineering contracts and carrying out the work, the decisions regarding the approval of track gauge and design of rolling stock, all protracted the completion of this second direct link with London and the Midlands.

Eight years were to elapse before the completion of Luton’s second station and line. Unfortunately the track-laying lost Luton its North Mill, the largest of the Domesday water-mills, which had to be demolished where the tracks crossed the mill site near to Mill Street.

On the eastern side of the New Bedford Road ran the stream that, before the old Domesday mill was demolished, took waters from the River Lea to the mill head of North Mill in Mill Street. In black and white, where does reality end and reflection begin?

This familiar bridge in New Bedford Road was built to carry main line rail traffic between London and Scotland in 1867. Although having sufficient headroom to clear the majority of traffic, the lack of it when Luton had a tramway system entailed the conductor pulling the trolley-bar down with a cord. At the same time he would shout in Lutonian, “Kee’ yer edds down unnda the bridge!”.

The coming of the railways had cut the town in half separating High Town from Bute Street and the remainder of the commercial centre. To placate the many irate people living in High Town who felt they had been left out on a limb, a footbridge was built spanning both railways. The bridge, which was officially opened on 28th Apri1,1868, gave access to both of the railway stations and Midland Road.

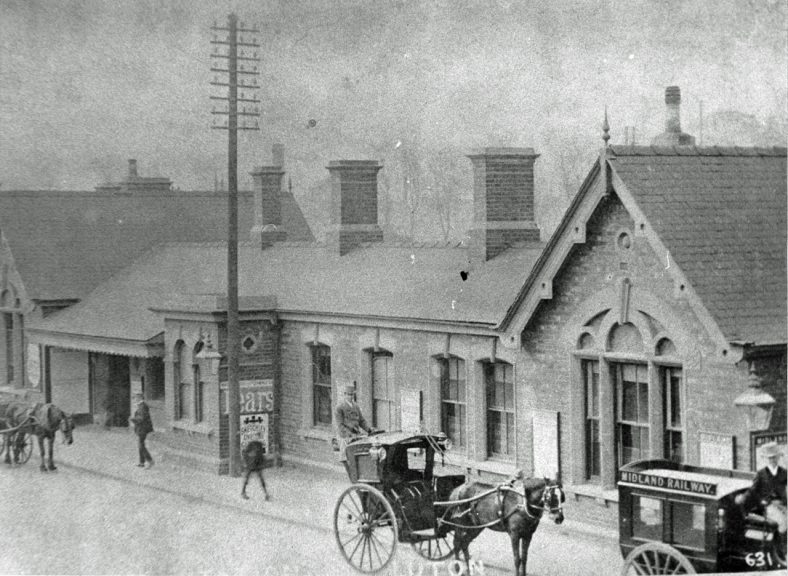

The Midland Railway Passenger Station was completed in the late 1860s and approached by a newly laid Private Road, named with astonishing originality, Station Road. It annoyed Lutonians who preferred the pre-railway name of the old road it crossed, Love Lane. The photograph shows the station as it was in 1910. Notice the hansom-cab waiting for fares and the telegraph pole.

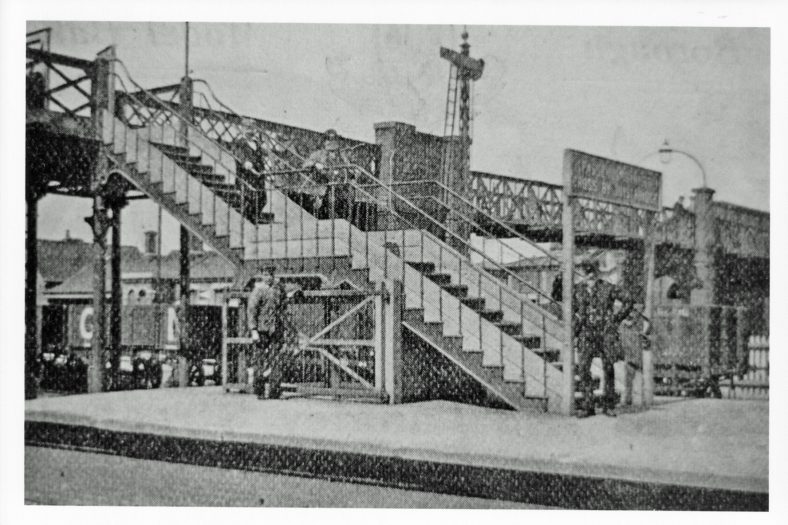

The lattice-work footbridge that spanned the L.M.S. and L.N.E. Railways was built to join Luton and High Town, giving access to the two railway stations on the way. This early photograph shows the steps leading down to the L.N.E.R. platform and the typical construction of the bridge.

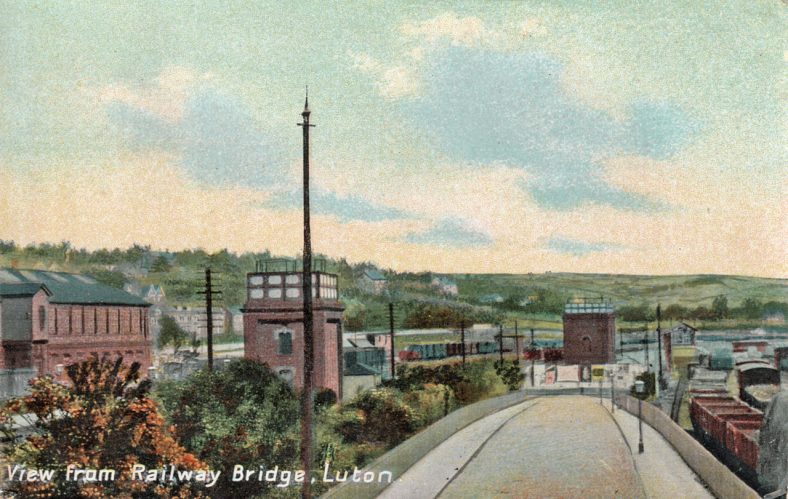

Looking down Station Road from the railway passenger footbridge towards Hitchin Road in 1908, both of Luton’s railway lines can be seen, Midland to the left and Great Northern to the right. The sidings of both companies can be seen to contain numbers of trucks and wagons. The background scenery, made up of fields and open spaces, underlines the country aspect of early 20th century Luton.

The railways quickly became an accepted way of life for commuters and pleasure passengers alike, but probably the greatest beneficiaries in the early days were those involved in the hat industry. Manufacturers soon got into the routine of preparing cartons of hats for late afternoon collection by railway company drays for overnight dispatch to London fashion outlets and ship ping ware-houses. Empty cartons, crates and plait were returned by early morning trains the next day. Over forty horse-drawn wagons belonging to the two railway companies were engaged daily on this task causing heavy congestion in the centre of the town where most of Luton’s hat factories were situated.

The Great Northern drays are loaded with crates of straw hats collected from hat factories in the centre of Luton ready to be dispatched to fashion houses in London, circa 1890.

The railways were also responsible for improving the delivery of coal to Luton’s domestic and commercial markets, the Gas Works for instance, for until coal was transported by rail from the mines it was moved by barge and wagon, a slow and expensive method of handling, which was superseded by direct rail delivery to the coal-merchants’ yards, almost in the centre of the town.

With an established railway system already in existence, the opportunities for “New Industries” being encouraged to settle in Luton by the Council became obvious, with goods yards and sidings available capable of handling industry’s raw materials and finished products. Several companies, like Vauxhall Motors and Bamforths for instance, who made Luton their new home, installed sidings on their own factory sites. As the population of Luton grew, passenger and goods traffic expanded too, especially between the wars when paid holidays became the fashion and it became easier for the working population to take holidays. Arrangements for sending luggage in advance and the great crowds of holiday makers thronging the Luton stations and Station Road at “works shut-down weeks” underlined the pleasures the railways had brought. The future looked so bright for the railway that the Midland Station was virtually rebuilt in 1937.

During the Second World War, both the London and North Eastern Railway (L.N.E.R.) and the London, Midland and Scottish Railway (L.M.S.) made a significant contribution to Luton’s war effort by transporting much of the wartime output of local factories. After the conflict, the railways became vital in supporting the great post-war export drives, especially that of Vauxhall Motors Ltd, who not only had sidings at the Luton factory but also an extensive marshalling yard at Oakleigh Park where crated vehicles were held prior to world-wide delivery.

After the 1945 General Election, the Socialist Government under the premiership of Clement Attlee embarked on a programme of nationalising the utilities and basic industries. The nation’s railways were included in the sweeping changes this policy brought about. It meant rationalisation of services, new liveries, from uniforms to trucks, and after the Instrument of Nationalisation, on 1st Jan 1948, the appearance throughout the railway system of signs proclaiming “BRITISH RAIL”. A fourth platform was added to the ex-L.M.S. station in 1960, which, with the addition of new diesel-engined trains, provided a better service between Luton and London. However, due to the decline of traffic on the old branch line brought about by the increase in ownership of motorcars and greater use of road transport for moving goods, the future of the Luton, Bute Street Station was in the balance. The Dr. Beeching Report on Railways sealed the fate of Luton’s oldest railway, and passenger services ended there in April 1965, to be followed by complete closure in June 1967. Although the station site with its associated buildings has been cleared, some of the track between Luton and Dunstable still remains and only the future knows the end of Luton’s railway saga!

LUTON WATER COMPANY.

In 1833 plans were well advanced to use coal-gas as an illuminant in Luton, but another forty years would elapse before piped water supplies would be connected to local homes and commercial premises. There was a move to provide Luton with fresh water in 1861, but because of local opposition and reticence on the part of financial backers, this initial try at forming a Water Company was abandoned. At this time, the supply of water, probably man’s most vital commodity, relied on its acquisition by collecting rain from the roofs of buildings and storing it in butts or underground cisterns; taking it by bucket or jug from rivers and ponds; or by tapping underground sources, for example wells and springs. Each of these alternatives involved the carrying of some sort of vessel to and from the point of supply, a far cry from the turning on or off of today’s water-tap.

Because of the amount of water drawn from wells by industry and the population’s needs, the water table or depth of water below ground has dropped considerably since pre-industrial times. This meant that in the mid 19th century common wells or well-pits did not have to be dug too deep, although naturally the higher up the slopes of the Lea valley that wells were dug the greater the depth necessary before water was reached. For some of the really deep wells, for breweries for example, the shafts had to be ventilated by boys using bellows and air-pipes to overcome the danger of carbon dioxide given off by the diggers. The usual diameter of the old wells was three feet, for they were excavated and lined by hand with open-jointed brick-work.

As mentioned, the depths of wells varied and in the shafts where the water table was high water could be drawn by means of a bucket and well-hook attached to a pole. In the deeper wells water was drawn up in a bucket, raised and lowered by a windlass mounted on the wellhead.

A typical wellhead fitted with a windlass to raise and lower the bucket when drawing water. The head is also equipped with a hinged plate to keep out dirt and debris. This is the type of well that stood at the junction of Castle Street and Victoria Street.

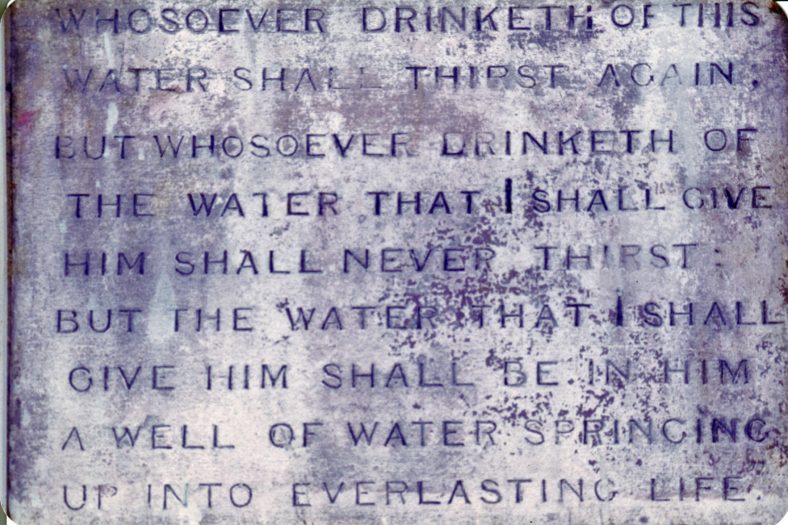

In the mid 19th century many homes were built in Luton to cater for the increased number of hat industry workers. They were often erected in blocks or terraces where it was common practice to provide a communal yard or garden in which a well would be sited. The Ordnance Survey Map of 1880 also shows several yards possessing a pump. They would probably have been simple single acting plunger pumps, usually fitted with a leather washered valve. Pumps of this type may still be seen standing at the kerbside in isolated villages today. Often the position of wells were marked with a plaque containing a religious text or quotation, for example, “He shall lead them unto fountains of Living Water. Revelations, Chapter 7 Verse 17”. The only known surviving wall plaque of this type left in Luton is to be found in a private car park belonging to the office premises at the junction of Castle Street and Victoria Street. The floor of the car park covers the site of the well-head but the plaque shows the well-orientated biblical text of St. John, Chapter 4,Verses 13-14 :-

“Whosoever drinketh of this water shall thirst again: But whosoever drinketh of the water that I shall give him shall never thirst; but the water that I shall give him shall be in him a well of water springing up into everlasting life”.

(Note – since this plaque is in a private car park, permission must be sought at the Offices’ reception desk before viewing).

The last remaining well plaque in Luton, containing a religious text from the Gospel of St. John, relating to wells and water.

With a steadily deteriorating health situation due to poor sanitary conditions, questionable sewage disposal and dubious water supply, it was only a matter of time before piped water supplies became a must and yet when an Act of Parliament “for better supplying with Water the Town of Luton” was passed on 26th May,1865, the scheme was opposed by the Local Board of Health, the administrators of Luton before the Borough was Incorporated in 1876.

Copy of the Parliamentary Act requesting Queen Victoria to approve the construction of the Water Works.

The first shareholders meeting of the Luton Water Company must have seemed like deja vu, so similar was it to the first meeting convened by the Luton Gas Company 30 years previously. The meeting was held on 21st April,1868, at The George Hotel, with sixteen shareholders being present. The Chairman of the inaugural meeting was Mr. Edward Lucas, a branch manager at Sharples, a local bank that later became part of Barclays Bank. He was elected as a director of the water company, with the obvious thought in mind of him keeping a watchful eye on the company finances. This he did for six years, until he was “transferred to a bank outside Luton”.

The next Chairman, Mr. Frederick Brown, wasted no time in getting things moving, for at the second Company meeting, this time in the Town Hall, he announced that “The buildings and reservoir are nearly completed and the greater portion of the principal street mains have been laid”. It certainly emphasises the enthusiasm within the company, for within the first year all the buildings had been planned, designed, built and equipped with the necessary steam engines and pumps. The first of the company’s wells had also been sunk to a depth of 322 feet, having been tubed down the first 100feet. While this substantial programme was being carried out at the Works in Crescent Road, most of the major thoroughfares in the town had been trenched to receive water mains in the anticipation of customer demand and a large reservoir completed on Hart Hill.

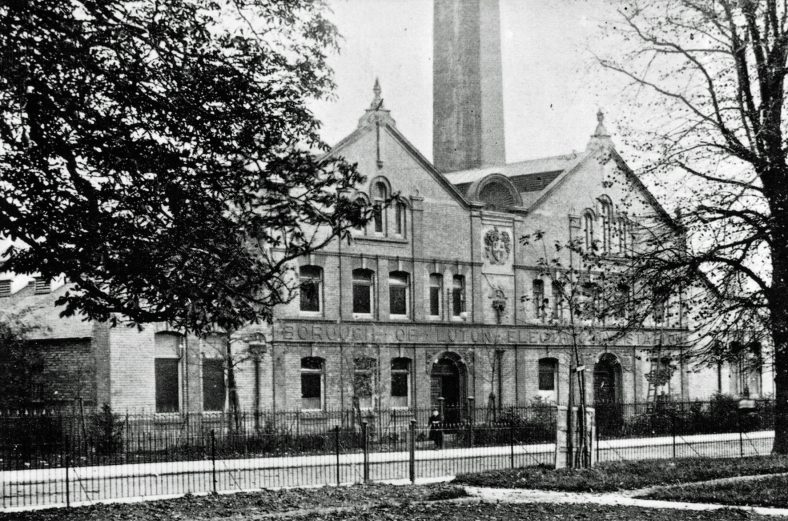

The buildings of the Luton Water Company in Crescent Road prior to their demolition in the 1970s. The two outer blocks were in use for almost a hundred years.

The residence of the Chief Engineer was next door to the Works, ensuring he was available to cope with any emergency. He even had a capped trial bore hole in his front garden!

Early in 1870, trials of the pump and associated steam engine proved to be highly satisfactory, producing water of very good quality. The Directors were delighted, especially when the Midland Railway Company and the Local Board of Health wanted to enter into contracts for the supply of water. The trials had gone so well that on 6th April 1870 the Directors accepted the Works from the installation contractors. The Luton Water Company was in business. Within three months, over one hundred and twenty hotels, public houses and domestic premises had asked to be connected to the mains. It was just the start of an avalanche of requests by customers to be connected. Unlike coal-gas, which was sold by metered quantity, the price of water depended on the ratable value of the property and was charged on a half-yearly basis. This figure was calculated from the size of the building and the number of water outlets or taps it contained.

One of the concerns of the directors during the 1870s was the escalating price of coal caused by increased wages and transport costs from the pits. They realised that higher water-rates could easily deter prospective customers, some of whom still looked on piped water as an overated luxury. Economy measures were taken in the works, principally by the fitting of “Patent Economisers” to save fuel used by the boilers. By this means, the price of water sold to the customers was held, and the share-holders kept sweet by the payment of a five per cent, tax free dividend!

A period of increased growth in the number of customers and connections followed and as a result in the early 1880s the Company erected a new pump-house and machinery at the Crescent Road works and bought an extra plot for building expansion on the Hart Hill site. With water sales booming and the company’s forecast looking sunny, worry for the share-holders came with the noticeable drop in the yearly local rainfall figures. The rainfall in 1882 being 30.6 inches, the following year it was 27.43 inches and in 1884 had dropped to 19.51 inches. Luckily, the three dry years did not materially affect the yield of the wells.

As the 20th century approached it became clear to the directors that because of the demand for water by Luton’s rapidly growing population, especially in the older parts of the town, and insufficient “head” or pressure of water to supply the higher regions and Stopsley, that firstly, more water would have to be produced and secondly, a way to increase the pressure in the new areas around London Road and High Town needed to be found. To meet these needs, further wells were bored at Crescent Road, making a total of four, with plans put in hand to build two Water Towers, one at Bailey Hill and the other on land adjacent to the reservoir at Hart Lane. In 1900 the Hart Hill tower was the first to be completed followed by the Bailey Hill tower a year later.

Hart Hill Water Tower, erected in 1900 and now a Grade II listed building. Prominent on Luton’s eastern horizon.

Bailey Hill Water Tower, completed in 1901 and now a Grade II listed building. A prominent feature on Luton’s western skyline.

Although the hat trade had been responsible for Luton’s growth in the 19th century, it was the results of the New Industries Committee that brought engineering companies and their associated workers to swell the population in the twentieth. Yet again the demand was for more water and in 1934 a new site at Runley Wood was purchased, where a 7ft diameter, 250ft deep well and two 650ft deep bore holes were dug. The need was temporarily assuaged, but history repeated itself in the 1950s when a new pumping station was opened at Friars Wash. Water from the Friars Wash wells was fed to a new reservoir at Chaul End, which not only served Luton but Dunstable too. With Luton still growing, yet a further reservoir was constructed at Whitehill, Stopsley. The height of the two new reservoirs above sea level gave enough pressure in the town mains to render the two Water Towers, accepted parts of Luton’s sky-line for almost a century, obsolete. Once again, in the 1960s, dropping water levels caused the search for water to be continued and in 1964 Grafham Water, a large man-made lake and natural reservoir drawing water from the River Great Ouse, was used to augment Luton’s supplies. On 1st January 1973, The Luton Water Company was taken over by the Lee Valley Water Company after just over a hundred years of public service.

LUTON ELECTRICITY UNDERTAKING.

The late 1870s saw electricity first used to illuminate parts of the Thames Embankment with arc lamps and although seen by many as just another gimmick, businessmen with an eye to finance could see the potential of this challenge to the already established gas industry. The Luton Borough Council, which had only been founded in 1876, grasped the significance of running a municipally owned Electricity Undertaking, for they could see that cheap electricity would not only bring lighting and heating within the reach of Lutonians’ pockets, but also provide the power to run a municipal tramway system too. Further, they saw that by offering low-priced rates, factories from other parts of the country wishing to expand or relocate would be encouraged to settle in selected industrial sites in Luton. It was consequently agreed that a factory for the generating of electricity would be built if and when a convenient site could be found.

In 1897, following the death of the Rev. James O’Neill, the Vicar of Luton, St. Mary’s had a new vicar, the Rev. Edmond Mason, who being modern in outlook, was anxious to dispose of the mellow old 18th century vicarage that stood in large grounds adjacent to the “Parish Church”. Unfortunately, vigorous protests and petitions by parishioners and townsfolk were to no avail and the rambling old building was superseded by a new vicarage in Crawley Green Road.

Following the death of the Rev. J. O’Neil, the new Vicar of Luton Rev. Edmond Mason threatened not to take up the living unless the old vicarage was replaced with a modern building. A deaf ear was turned to protests and petitions and the rambling old building was finally demolished in 1907.

The ancient vicarage with its splendid public gardens was just the site the Corporation had been looking for to build the proposed electricity generating station and a new “Borough Yard” for the storage of road maintenance and cleansing vehicles. When built, the Yard also contained stabling, smithing facilities and a food store for the Corporation’s horses. Before a start could be made on the construction of the new works, an access road had to be laid between Lea Road and Church Street, known today as St. Mary’s Road. The erection of the Electricity Station, as it was called locally, started in 1900 and the first phase completed early the next year. In July the installation was opened by a leading physicist of the time, Lord Kelvin, a Fellow of the Royal Society, who reputedly stunned all the official guests present by admitting in his opening speech that he “didn’t know what electricity is”.

Taken in 1903 from St Mary’s churchyard looking across the newly laid St. Mary’s Road to the Phase 1 buildings of Luton’s Electricity Station.

Starting in a small way, the company began with only 60 consumers and yet within six years had grown to over 300, necessitating major extensions to the Undertaking’s buildings and generators to cope with the extra demand. At this time, the old vicarage was demolished and the remains of the Public Gardens, an adjunct to the adjoining churchyard, cleared. At the back of the Borough Yard stood the cooling towers of the Electricity Station, used to condense the spent steam and hot water from the engines driving the generators. The first of these towers were tall, wooden box-like structures coated in tar to prevent rotting. The cascading water in the towers was a constant source of interest to children who would stand and watch them from the lattice bridge in nearby Pondwicks Path. Because of the high maintenance costs of the original wooden towers they were replaced in the early 1930s by two cylindrical concrete towers which, although supposed to be of the latest design in condensers, caused the Corporation almost continual trouble by the public’s many complaints about the condensate, falling as light rain on most of the surrounding streets. Conditions were especially dangerous during the winter months when roads and pavements were often covered with a thin layer of ice.

View of the ancient footway, Pondwicks Path, that ran between Pondwicks Road and Church Street, bordering the boundary of the Electricity Station property. The lattice bridge crossed the siding bringing the coal wagons to the Electricity Works. Note the cooling tower in wartime camouflage.

The two concrete cooling towers of the Electricity Station, seen from St. Mary’s churchyard.

A further irritation to nearby residents came from the proliferation of coal dust when the automatic coal bunker was being used and the fallout of airbourne smuts when the Lancashire boilers were being used. These pollutants were particularly annoying when freshly washed clothes were hung out to dry on Mondays, the conventional washday morning. As with the distribution of gas and water, the supply of electricity to the customer brought considerable inconvenience to the citizens of the town as streets and roads were disrupted by the hand-laying of miles of mains cabling by navvies, making people grumble and think, “Is it all worth it?”.

Aerial view of the Electricity Works and Borough Yard. Note the water cooling towers, Bamforths Boiler-makers, the many terraced houses and the east end of St. Mary’s Church. This area has been re-developed as Power Court.

For the first few years, Luton rate-payers received little benefit from the investment the Corporation had made on their behalf, but soon after, capital repayments had been made, profits increased from the sale of electricity and thus greatly reduced the Town Rate bill. By the end of the 1930s the relief amounted to £10,000 per annum. One of the hidden advantages of municipal electricity manufacture was that it provided a source of cheap power to run the Corporation Tramway System. Apart from the local domestic market, the Luton Electricity Undertaking supplied power to The North Metropolitan Electric Power Supply Company for their St. Albans and Harpenden districts, also to the towns and surrounding villages of Ampthill, Aylesbury, Dunstable, Flamstead, Leighton Buzzard and Linslade.

In the early 1930s the equipment in the Electricity Station needed to be upgraded and the change was made from direct to safer alternating current. At the same time, Luton was connected to the Central Electricity Board’s National Grid via the grid station in Kimpton Road enabling electricity to be sold during periods of low demand and bought when demand was high. Between the wars gas was gradually phased out as an illuminant in homes and streets giving way to the brighter electric lamps. The battle for customers raged in George Street between the sales departments of the Gas and Electric Companies, each with their own prestigious showrooms.

The Easter Electricity Showrooms In George St, (far left).

Following the election of a Socialist Government after the second World War, the Luton Corporation Electricity Undertaking was nationalised on 1st April 1948 and became absorbed into the Eastern Electricity Board.

Comments about this page

Not far from Crescent Road is Back Street at the back of High Town Road in Luton. Is there any photographs of Back Street as my great, great, great grandfather resided there in the early 1800’s.

Kind Regards

John Boutwood

Add a comment about this page