Luton Past – Chapter 2 – Highways and Byways.

An examination of the chronology will show there has been no scarcity of historic events in Luton’s immediate past despite the often-voiced view by older Lutonians that the town has little to offer historically. True enough in some respects, for Luton, due to its location tucked in a cleft in the Chiltern Hills and the partiality of Romans to join towns together with straight roads, remained an insignificant market village in southern Bedfordshire until brought to life by the coming of plait hats and industries. Until the beginning of the 17th century Luton was virtually unknown with no recognisable or nationally regarded castle, battlefield, monastery, grand civic buildings or dynamic administration like most contemporary county towns or cities.

The growth of Luton began in the early 1800’s in the backwash of the Industrial Revolution, the Napoleonic Wars and the surge of Victorian innovation. With this growth and expansion came the buildings that had until then been missing, for example a Town Hall, Public Library, a new Corn Exchange, Inns, Hostelries and shops. The erection of business premises and new shops tended to dictate the shape of the town centre as it grew, with the outskirts comprising several insular districts and hamlets. In the period between the first and second World Wars, the layout of Luton was almost static, the centre being a warren of small but interesting streets, businesses and houses, which the townsfolk found “comfortable to live with”. The last thirty years (Ken wrote this in 2000) has seen the town change quite dramatically with the loss of many familiar and cherished buildings, especially in paving the way for the Arndale Centre and around the town core. However, in spite of the alterations and rebuilding, those wishing to refresh past memories may find that studying Luton’s street names may prove to be a useful aide-memoire not only to local history but national history too.

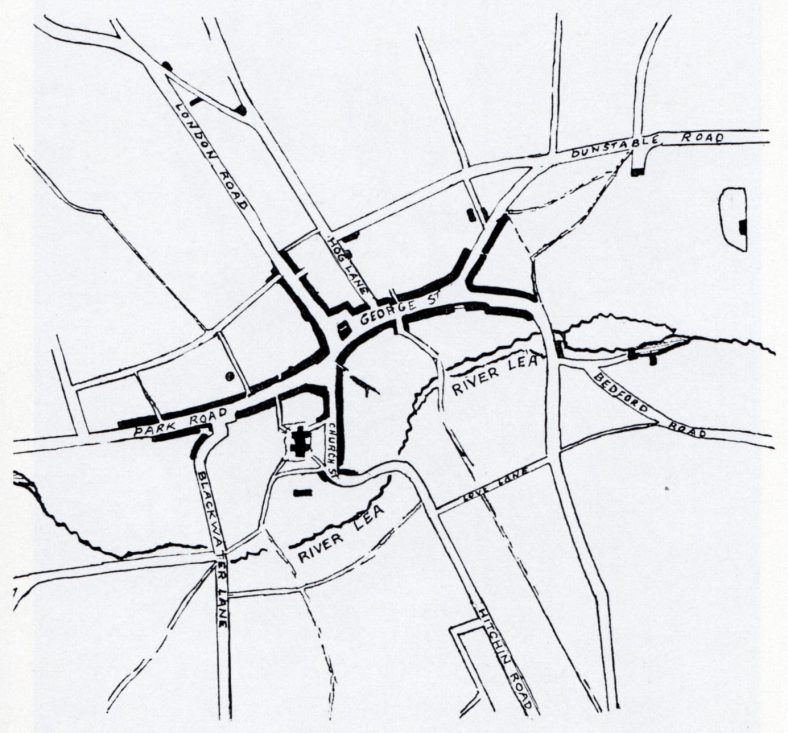

A copy of an early Luton street plan in a booklet published by the Luton Scientific, Literary and Artistic Club in 1890 shows the extents of Luton as it was in 1815. At this time there were approximately 3000 inhabitants living in the town and only ten roads, streets and lanes.

Map of Luton, 1815, as produced by the Scientific, Literary and Artistic Club. The position of the main streets had been established at this time and have changed little over the years.

The street names followed the typical town and village practice of indicating the direction of the next major town or city along a traveler’s route, as with Bedford Road, Dunstable Road, Hitchin Road and London Road.

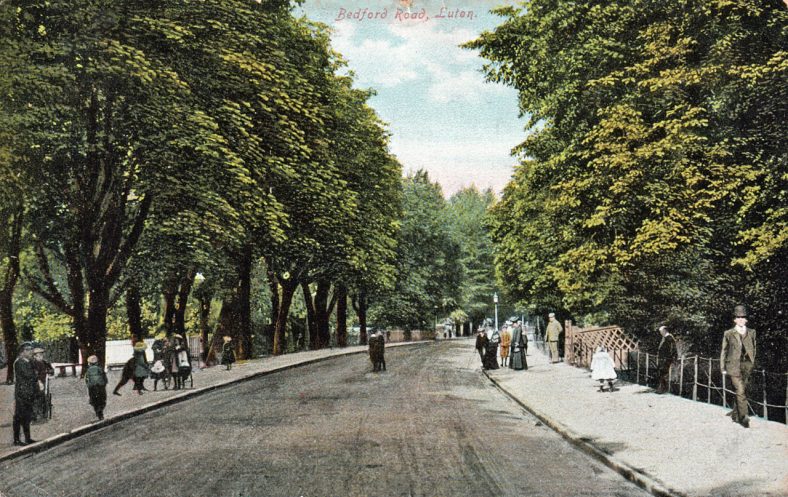

The New Bedford Road.1906. The approach to Luton from the North, flanked by horse-chestnut trees. The River Lea flows on the left, with water that, before the coming of the railways, used to feed North Mill channelled to the right.

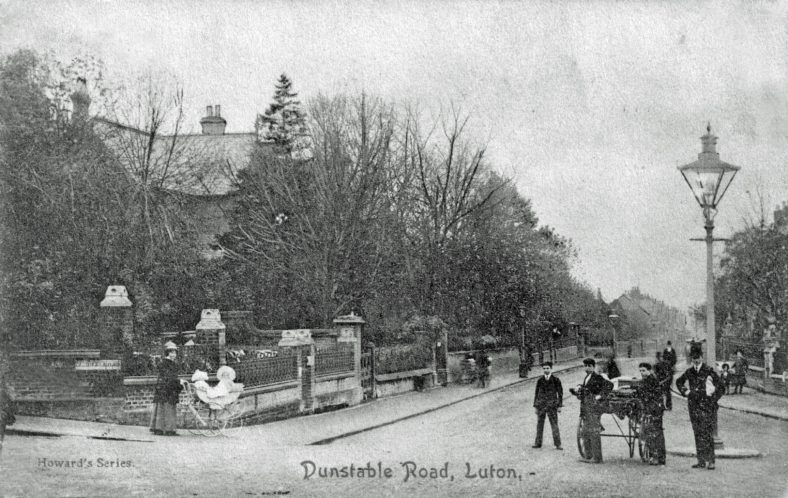

Dunstable Road,1905. The junction with Stuart Street, Cardiff Road, Inkerman Street and Upper George Street. The only traffic on one of today’s busiest spots are perambulators and a hand cart. Note the ornate gas-lamp with supports for the lamplighter’s ladder.

Luton from Hitchin Road.c1950. Looking across the River Lea valley from Kenneth Road showing the parting of the road into Hitchin Road on the left and High Town Road to the right. One of the steepest sections on the road to Round Green.

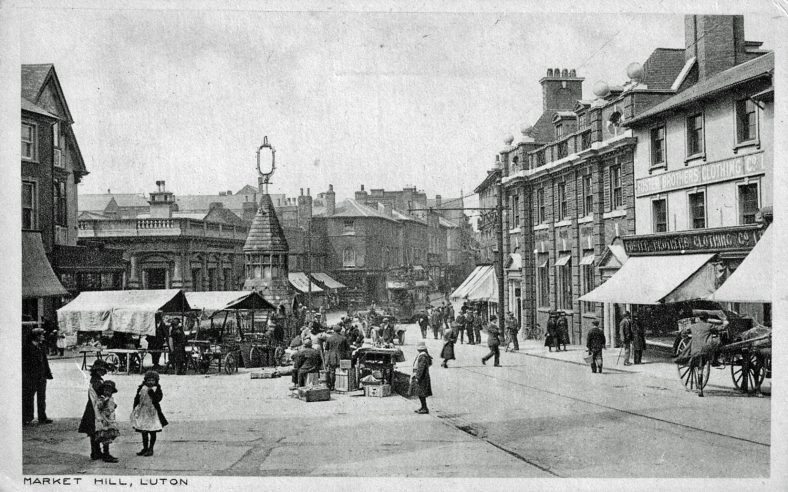

Other names, by common knowledge, showed the way to near-by local land-marks or facilities, for example Church Street, Market Hill or Cheapside. Cheapside was a very apt choice of name for this street since it comes from an Old English word meaning market, which in Luton’s pre-Arndale days is where the market was. Geoffrey Chaucer mentions a similarly-named London Market street in “The Cook’s Tale”, from “The Canterbury Tales”, when writing of an irresponsible apprentice who worked in a shambles there:

“Whenever any pageant or procession

Came down Cheapside, goodbye to his profession.

He’d leap out of the shop to see the sight

And join the dance and not come back that night!

The Market Hill, c.1920. Fruit, Flower and Vegetable stalls clustered around the Corn Exchange and Ames Memorial Fountain in the traditional market place, before the widening of George Street.

With growing numbers of houses and streets being built due to industrial expansion in the 19th and 20th centuries, names had to be found to identify them for postal and administrative purposes. After the Inauguration of the Borough in 1876, this task was carried out by a Council Committee which included the Town Clerk and the Borough Engineer who looked after the general administration of highways.

In the nineteenth century Luton’s influence and affluence grew rapidly, as did the spread of housing both in the town, surrounding districts and hamlets, necessitating more and more roads to service them. This link-up of districts by roads and streets produced names for them such as Biscot Road, Limbury Road, High Town Road, Round Green, Crawley Green Road and New Town Road etc. Later, the choice of place-names was broadened to include county and town names from further afield, for example, Dorset, Essex and Surrey Streets and Cambridge, Hastings and Windsor Streets.

The monarchy too has provided many a regal name for several of Luton’s streets, especially in the older parts of the town, for example Adelaide Street, named after Adelaide, Queen of King William IV; Regent Street, named after the Prince Regent, son of King George III, later crowned King George IV; Victoria Street and Queen Street were named as a compliment to Queen Victoria; Albert Road owes its name to Albert, Prince Consort, Queen Victoria’s husband; and finally, Alexandra Avenue, named after the Princess of Wales who later became the Queen of King Edward VII.

Saints and Poets provide many a Luton street with an identifying name. Saints aplenty are to be found to the north of Montrose Avenue, whilst the Poets are huddled between Lewsey Road and Poynters Road. There are exceptions to both of these categories in the southern part of the town, where for instance, St. Pauls Road, Tennyson Road and Pomfret Avenue may be found. Pomfret Avenue is of special interest since the Rev. John Pomfret, 1667-1702, was a local poet, born in the Vicarage of The Parish Church of St. Mary. He was the son of the Rev. Thomas Pomfret, controversial Vicar of Luton. John himself was no stranger to controversy and although comparatively unknown today, a book of poems published in 1701 entitled “Choice”, became widely read. One of the passages in the volume contained the inference that “more happiness was to be found in the pleasures of a mistress than a wife”, which understandably upset the clergy and puritanical intelligentsia of the day. A quotation from another of his poems, “Reason”, one of his more acceptable works, reads, “We live and learn, but not the wiser grow”.

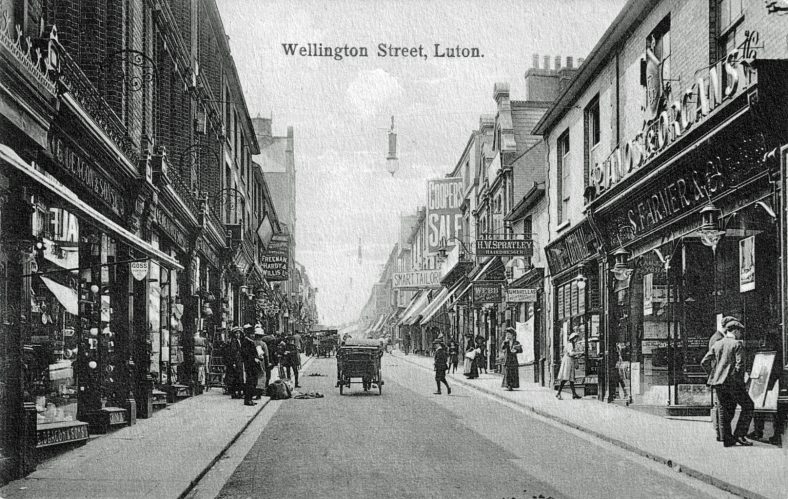

Military men and foreign campaigns also feature in Luton’s street names. Memories of The Battle of Waterloo and the Iron Duke haunt Wellington Street, laid out in the early 1820s; while General Charles G. Gordon of Khartoum, killed in 1885, is commemorated in the name Gordon Street, just behind the Town Hall.

Wellington Street in pre-war 1914 was Luton’s premier shopping street, packed with a huge variety of shops. It was possible to purchase anything from a piece of Goss china to an organ or alternatively just “window shop” in the smart fashion houses. Notice the electric lamps suspended over the roadway.

Nearby are streets bearing the names of two of the bitterest battles fought during the Crimean War. Those of Alma and Inkerman, they also bring to mind the street named after Lord Cardigan, who led the Charge of the Light Brigade and memories of the Thin Red Line. Several local men served in the Rifle Brigade during the Crimean Campaign and the Luton Times, Luton’s first weekly newspaper, printed copies of their letters home which made compelling reading for news hungry Lutonians.

Peel Street, a small cul-de-sac formed by building a new telephone exchange adjoining the old Post Office, originally ran between Dunstable Place and Wellington Street. It was named after Sir Robert Peel, the Home Secretary who established the Metropolitan Police Force in 1829. His ideas on policing were adopted throughout the country and his policy of using the police as a law-keeping force with a separate identity to the military resulted in the introduction of a uniform comprising top hat, frock coat and white trousers. When policemen first appeared on the beat they were nick-named Peelers and later Bobbies after Sir Robert. As a tail-piece to this street, it is on record that, “a small lock-up for detaining miscreants” stood at the corner of Peel Street and Dunstable Place.

Modern-day Peel Street, associated for many years with police and law-enforcement activities, now a quiet backwater cul-de-sac off Wellington Street, reduced in length and stature by the erection of the Automatic Telephone Exchange seen in the background.

The sympathetic naming of streets in the Leagrave and Marsh Farm districts has enabled the Council to link town planning with local history by using the names of artifacts discovered when the area was being developed. Examples reflecting these finds are to be found as Arrow, Axe, Spear, Pottery and Sherd Closes.

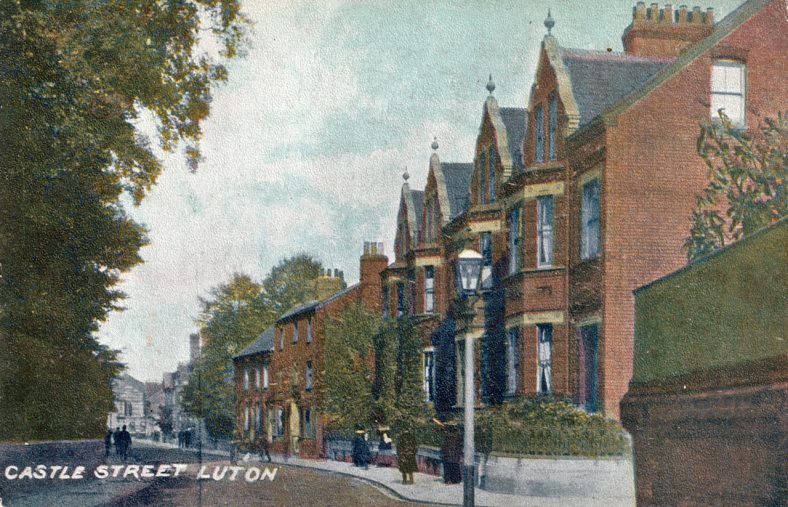

Today, Luton’s castles of yore are but misty shadows in the history of the town, but never-the-less traces of them are still to be discovered, cropping up in local street names. Castle Street itself contains the site of the first Luton castle. Built in 1139 by Robert de Waudari, a mercenary hired by King Stephen to support him against the country’s quarrelsome Barons. De Waudari was given the title of Lord of the Manor of Luton and built himself a simple motte and bailey castle, that is a defensive mound surrounded by a stout palisade and ditch. The boundary of the castle was roughly circular in shape, spanning today’s Castle Street, part of the University of Luton’s forecourt and the bus garage parking area opposite. By straddling the road into Luton sentries on look-out would have been able to watch the comings and goings of travellers posing a threat on the London Road. Fifteen years after the building of de Waudari’s castle, King Stephen came to an agreement with his Barons known as the Treaty of Wallingford, the terms of which included the banishment of all soldiers of fortune and the demolition and levelling of their castles. Apparently the demolition of the castle was not entirely completed, leaving part of the mound and ditch exposed.

The remains of the castle were finally levelled in the mid 1800s when preparations were being made for the erection of a large house known as Holly Lodge, one-time home of Henry Brown, a prominent local timber merchant. In 1964, when a factory for publishing and printing The Luton News was being built at the corner of Castle and Holly Streets, some of the palisade post-holes were exposed for a short time. Unfortunately the castle site had been cleared too well and nothing further of historical interest came to light. Today, Waudari’s Castle is just a memory reflected in the street name.

The wall, entrance to Holly Street and the tree-lined hedge to the right of this picture are built on the site of Robert de Waudari’s castle in Castle Street. The block of four palatial houses on the right were built at the turn of the century and when first erected included accommodation for servants.

Names normally be associated with a castle are to be found in the names Bailey Street or Bailey Hill in the Park Town area of Luton. In this context the name Bailey, Bailiffs or Bayley was, according to historian William Austin, one of the ancient manorial titles, dating from Norman times, that made up the district of Luton. It was closely associated with the Manors of Luton Hoo and the Brache. Although there are no manorial rolls in existence or physical evidence of a manor house, it is known that in 1638 this small seat was acquired by Sir Robert Napier, Lord of the Manor of Luton and the owner of Luton Hoo.

Because of exposure in recent publications, only brief mention will be made of the castle of Falk de Breaute or his unsocial behaviour. Court Road, birthplace of Dr. John Dony, a highly regarded Luton Historian, was one of the streets cleared in the Lea Road and Vicarage Street area during the demolitions and changes of the 1960s.

Court Road, c.1963. A view to St. Mary’s Church past shops and houses under condemnation of demolition, ultimately providing space for The University of Luton (remember Europa House?), Youth House, an Overnight Lorry Park and part of Luton’s in-completed Inner Ring Road.

The houses were built on the site of de Breaute’s castle courtyard, now occupied by Luton University. Falk came to England in the early 13th century as a mercenary, he was a friend of King John who made him Lord of the manor of Luton to establish his authority. Notice the similarity in this bestowal of power by the Sovereign “when it suited” in the cases of Waudari and de Breaute. The armorial bearing and crest that Falk carried on his surcoat, shield and helmet was the griffin, a heraldic beast with the forepart of an eagle with upturned ears and the hindquarters of a lion.

De Breaute was heartily disliked by the populace and caused trouble wherever he went, diverting the course of the River Lea to prevent the Church Mill from working, draining the Pondwicks fish-ponds belonging to the monks of St Albans Abbey and flooding Luton Church’s wheat-fields. On marrying a young widow he moved to an estate by the banks of the River Thames in south London, taking his armourial bearings and crest with him. His residence was known as Falk’s Hall, which in time and by usage became corrupted to Vauxhall. Centuries later the area became renowned for the Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens, a favourite venue of King Charles II. The wrought iron entrance gates to the gardens displayed Falk’s griffins as a decorative feature.

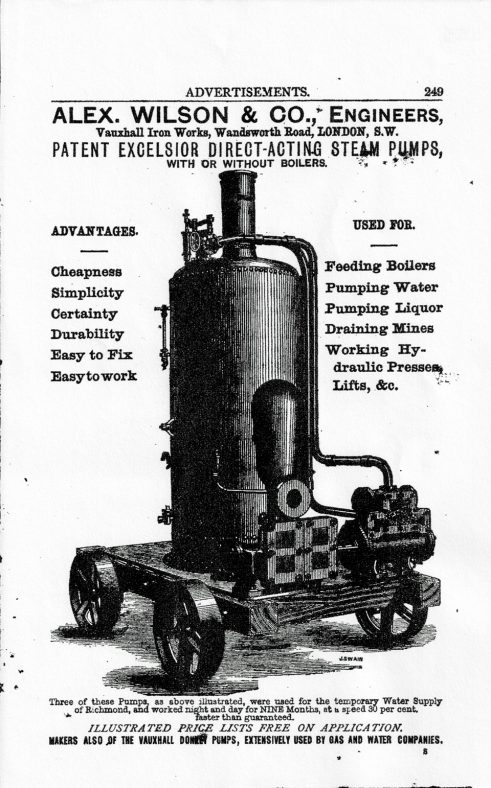

In 1857 Alexander Wilson, a Scottish engineer, started a company called Vauxhall Iron Works in the Wandsworth Road, London, to manufacture steam pumps and small marine engines. Wilson adopted the griffin motif as the company trademark on the Iron Works’ products.

This advertisement for Alex. Wilson & Co., shows one of their Patent Excelsior Direct-Acting Steam Pumps that appeared in “The Gas and Water Companies Directory for 1880”. Did the mobility of this cast-iron wheeled pump and boiler trigger thoughts of a motor vehicle?

At the turn of the century, the need for more business caused the company to diversify and experiment with petrol engines propelling boats and then turned its attention to making motor-cars. At the same time the lease expired on the Wandsworth factory and taking advantage of the benefits advertised by Luton Council’s “New Industries Committee” moved to Kimpton Road in Luton. Although the company name was changed, ultimately becoming Vauxhall Motors Limited, the Griffin trade mark was retained. By an amazing coincidence Falk de Breaute’s personal symbol, after almost seven hundred years, had returned to within half a mile of his old castle yard in Court Road.

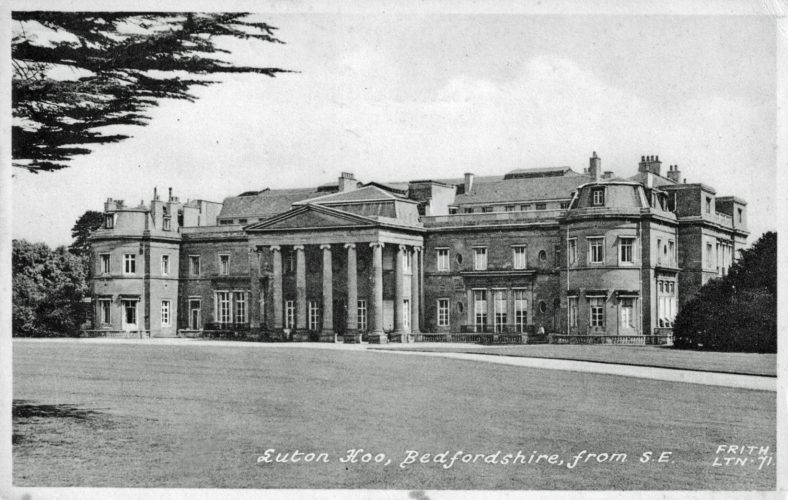

One of the governing factors that determined the growth of Luton on its southern boundary was the location of two large estates, those of Luton Hoo and Stockwood. Traditionally, Luton Hoo was the seat of the Lord or Lady of the Manor of Luton, whilst Stockwood was the seat of the long-established and powerful family of the Crawleys. Both of these groups of land owners have Luton streets named after them. The Napier family lived at the mansion of Luton Hoo for several generations between 1611 and 1761 and is perpetuated by the name Napier Road.

The Napiers were succeeded by the Bute family, the first of whom was John, the 3rd Earl of Bute, who owned an estate at Rothesay on the Isle of Bute, called Mount Stuart. He moved in high circles and in turn became Secretary of State, First Lord of the Treasury and Prime Minister. He died in 1794 and was followed by his heir Lord Mount Stuart, Marquess of Bute. By marriage, the elder son of the Marquess gained the title Earl of Dumfries and thus, from the Bute family, Luton acquired Bute Street, Dumfries Street, Rothesay Road and Stuart Street.

Rothesay Road, one of the roads named after the 4th Earl of Bute. As can be seen, it ascends a steep incline from Stuart Street and leads to the General Cemetery. Notice the milkman driving his horse-drawn delivery cart with a highly polished milk-churn in the back.

Strangely enough, after the occupancy of the Butes, Luton Hoo was occupied by a long string of owners, as yet not honoured in the same fashion. Following a disastrous fire in 1843, the Marquess lost interest in the estate, sold it to a Mr.Warde two years later and severed his connection with Luton. After his death the trustees of his estate provided a plot of land upon which to build The Bute Hospital. Mr. Warde too lost interest in the property and the rather dilapidated mansion-house was purchased by John Shaw Leigh in 1848. He spent a small fortune on the renovation of the fire-damaged house and improved the management of the estate.

It was the beginning of another dynasty ownership with the estate passing from father to son, John Gerard Leigh, on the father’s death in 1871. John Gerard’s wife outlived him and married His Excellency M. Christian de Falbe, from Denmark, in 1883. There was an unfortunate sting in the tail of this family story, for on the death of Madame de Falbe in December 1899, the estate passed to her first husband’s nephew Captain Henry Gerard Leigh, who died a fortnight later on the 7th January 1900, when he contracted severe pneumonia after riding to hounds. Imagine, Lord of the Manor for just over a fortnight!

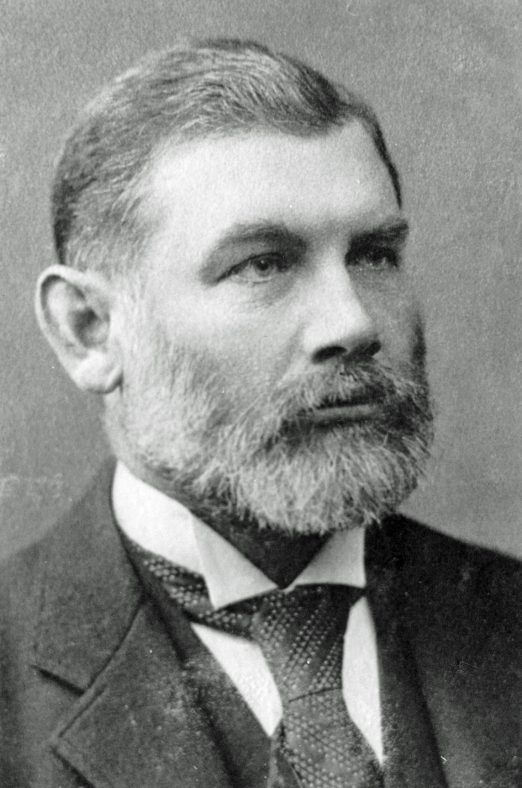

The Hoo stood empty until Julius Wernher and his wife Alice took up residence in 1903 and two years later a baronetcy was conferred on him.

Sir Julius Wernher, financier, mining magnate, owner of Luton Hoo and Lord of the Manor of Luton.

Sir Julius died in 1912 and seven years later, just after the Luton Peace Day Riots in 1919, Lady Alice unexpectedly married Lord Ludlow, becoming Lady Ludlow. In 1922, Lord Ludlow was unfortunate enough to sustain a riding accident resulting in fatal injuries after being thrown from his horse in the Hoo grounds. Shortly afterwards the Luton Hoo Estate sold a parcel of land bounded by London Road, Cutenhoe Road and the Kidney Closes (now known as Capability Green), forming the Ludlow Avenue Estate and in so doing provided another named road linked to Luton’s past history.

Luton Hoo is the quintessence of the English Stately Home beloved by its several owners and their many guests including British and Foreign Royalty and civic dignitaries. Originally built by Robert Adam in 1767 on the site of a previous house, the present building has been extensively modified having survived two serious fires that needed major repairs. The lives of the Hoo’s occupants have often been touched by tragedy and only time can unfold its future!

At the southern boundary of Luton, cheek by jowl with the Hoo estate, lies Stockwood Park, since 1708 the ancestral home of the Crawley Family. They had previously lived at the run-down fortified manor-house of Someries, but when Richard Crawley and his family settled into Stockwood they found that their newly acquired mansion was in only slightly better condition than the one they had left. In 1740 Richard’s son John had the old house demolished and replaced by a new Stockwood House, a grand and well proportioned building in which six generations of Crawleys lived out their lives.

Stockwood House was built in 1740 by John Crawley and remained in the Crawley family until 1945 when the house and estate of 263 acres were purchased by Luton Borough Council. During the second World War the buildings were occupied by the Queen Alexandra Hospital for Crippled Children which stayed until 1958. The house deteriorated and was demolished in 1964 leaving only the stable block, which is now used as part of Luton’s Country Craft Museum.

The Crawleys were wealthy landowners and property developers who, because of their local standing, held high positions in public life at both local and county level including two High Sheriffs of Bedfordshire, two Members of Parliament and several Justices of the Peace. Probably the most influential of the Crawleys was John Sambrook Crawley (1823-1895), who exchanged land he owned near High Town for the “waste”, or left-over part of the Moor on the laying of the Midland Railway. This exchange gave Luton its first public park, Peoples Park and John Crawley land for development on which he built Crawley Road and Francis Street, named after his eldest son.

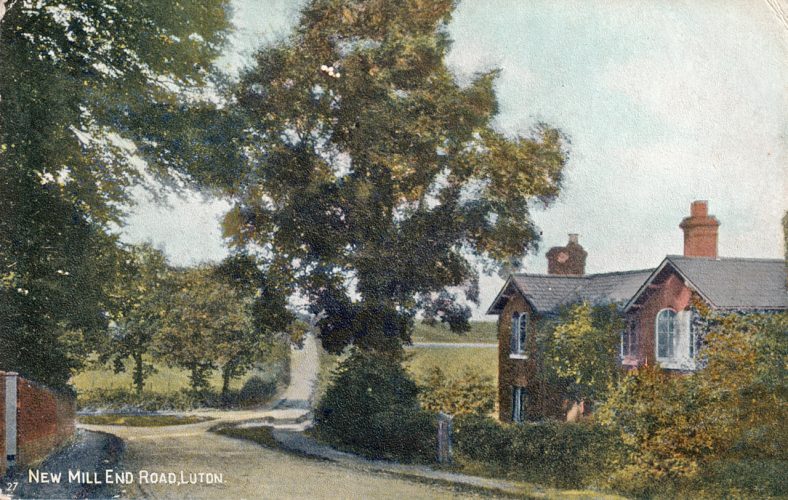

Street names connected with local trades and industries certainly bring a touch of the past to Luton’s highways and byways. Too often taken for granted, they underline the truth in the old adage, “familiarity breeds contempt”. As time, technical advances and fashion trends have changed the importance of the town’s business ventures, the associated number of street names has increased too. Milling grain, the first stage in the production of our daily bread, was in all probability the first of Luton’s staple trades and industries. The town’s watermills were driven by the sluggish waters of the River Lea and at the time of the Norman Conquest seven of them were listed on the Luton reach of the river. The location of only one of these old mills is officially marked by a street name, that of North Mill which stood close by Mill Street. This mill, the largest of the Domesday mills, was demolished in the late 1850s when the Midland Railway line was laid through the town. A further mention of a Domesday mill is to be found in the unofficial name for the Lower Harpenden Road which remains in many an elder Lutonian’s memory as New Mill End Road. This is a reference to the East Hyde Mill, the last of Luton’s Domesday mills still in existence and capable of being worked.

Today’s street plans and maps generally show this highway as the Lower Harpenden Road. This photograph taken in 1909 uses the title New Mill End to indicate the way to the Domesday Mill at East Hyde. The boundary wall on the left encloses the Luton Hoo Estate, and the road junction which includes Park Road, Gipsy Lane and Vauxhall road is currently submerged beneath Airport Way.

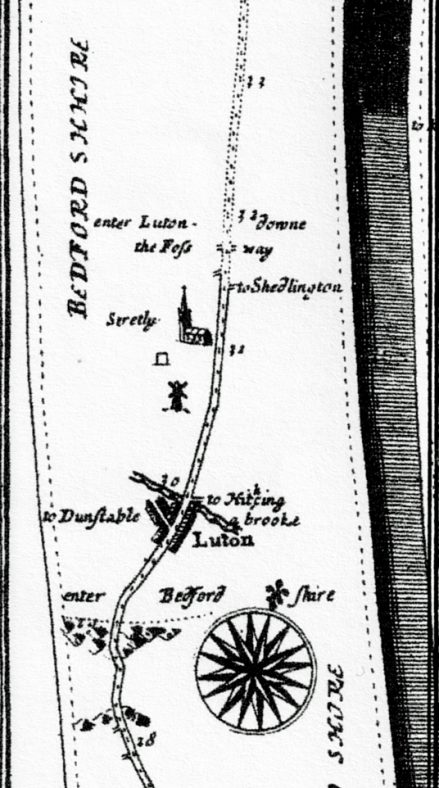

Whereas watermills are said to have been introduced into Britain by the Romans, the idea of using wind-power to turn millstones is credited to crusaders returning from the Holy Land having seen windmills whilst engaged in the Crusades in the 13th century. Probably the oldest of Luton’s windmills was the post mill at Biscot, which is clearly shown on John Ogilby’s map of The Road from London to Oakham, published in 1675.

Luton portion of John Ogilby’s strip-map, The Road from London to Oakham, Bedfordshire Section,1675. It shows the road from St Albans to Luton and thence to Bedford, the County Town. Luton is shown as a small town 30 miles from London at the junction of roads to Dunstable and Hitchin. Biscot Windmill is indicated but not Luton Church. The River Lea can be seen as a “brooke”.

They were called post mills because the body of the mill could be turned about an axle or post by means of a tiller, thus catching the wind to rotate the sails. The old mill at Biscot was of indeterminate age when, in a violent thunderstorm in 1841, it was struck by lightning and burned to the ground. Phoenix-like it was replaced by a smock mill in 1846. So called because the tapering body of the mill resembled a shepherds smock or shift. In this type of mill the sails were kept facing into the wind by means of a small auxiliary fan which, by means of crown and pinion gearwheels, rotated the dome complete with the sails. Milling went into a decline after the Great War and in 1925 the sails and fan of the Biscot Mill were removed. Whatever small amount of milling was to be done was carried out by driving the millstones with an electric motor. The mill was demolished in the late 1930s and its position marked by “The Biscot Mill (Hungry Horse)”, a public house and restaurant built on the site. Nearby is Millfield Road, where in more rustic times the miller grazed his pigs and sheep.

Biscot Mill, the last of Luton’s windmills. Standing in Biscot Lane, even in the mid 1930s when the houses in the “Saints” roads were being erected, the mill always had an eerie, isolated look. The picture shows the mechanisms on the sails needed to change from “feather” to “drive” and the auxiliary fan that turned the dome or cap and sails into the wind.

There were other mills in Luton, for example Rye Hill Mill and High Town Mill but these two are left unmentioned when it comes to historic street names. A post mill that became known through common knowledge stood at the corner of Kimpton Road and Windmill Road thus giving its name to the road, the Windmill Inn and The Windmill Trading Estate.

Brewing was for many years one of Luton’s staple trades but there are not many streets marking either brewers or the several large companies that made Luton famous as a brewing town. Buy-outs, takeovers and poor industrial relations have left little to mark this once staple trade in the street-names of Luton. One of the brewery owners who did have a street named after him was Thomas Burr, who in 1776 acquired a brewery in Park Street. He is doubly honoured for there is a Burr Street in High Town and a Burr’s Passage off Park Street West. Frederick Street and Reginald Street, both tributaries of the Old Bedford Road and Charles Street in High Town are named after members of the Burr family too. A further brewery orientated street name is to be found in the link-road between Castle Street and Chapel Street known as Flowers Way. This road borders the site of the old Flowers Brewery taken over by Whitbread in 1962, thus perpetuating its name.

Considering that between the 19th and mid 20th centuries Luton’s fame was based on the prolific manufacture of hats, there are remarkably few recognisable street names associated with the actual making of hats or bonnets to show for it. Two of them that are both comparatively new roads are Hatters way and Milliners Way, although Luton Borough Council does highlight Plaiters Lea, a general area where former hat factories were situated close to the river, in its publicity literature. Despite the dearth of hat related streets, manufacturers names are not too hard to find, as shown in the following selection:

Plait Dealers:- John and Thomas Waller, as in Waller Street Mall, The Arndale Centre; Mr. Coupees, as in Coupees Place, a cul-de sac of Castle Street.

Hat Manufacturers:- Mr. H. Durler as in Durler Gardens; Mr. A. Warren, as in Warren Road; Mr. K. Woodbridge, as in Woodbridge Close.

Bleacher & Dyer:- Mr. T. Lye, as in Lye Hill.

Inventor of Hat Sewing Machine:- Mr. E Wiseman, as in Wiseman Close.

The location of engineering companies has not provided the town with a prolific selection of memorable street names, a pity, especially now that so many of them have become part of Luton’s Industrial Past. The exception being Vauxhall Way, part of the Eastern Bypass, representing Vauxhall Motors and the car industry. The last of Luton’s staple trades to be mentioned in this chapter is included because of the many activities associated with aeroplanes, flying and Luton Airport. Officially opened in 1938, the airport has been host to several companies involved with aircraft manufacture and use. Memories of the well-known factory of the Percival Aircraft Company Ltd. and the name of some of the famous aeroplanes made at Luton Airport may be found in the names of the service roads, which include Percival Way, President Way, Prince Way, Proctor Way and Provost Way.

In Leagrave, Hewlett Road is a reminder of the early days of flight before the Great War when Mrs. Hewlett, the first woman in the world to hold a flying license, and her partner Gustav Blondeau, made and flew aircraft from their factory the Omnia Works off Oakley Road.

Hewlett Road, a tributary of Marsh Road cannot be described as photogenic. The derivation of its name is virtually forgotten, there is no plaque to act as a reminder and yet it commemorates the first aviatrix in the world to hold a Flying Licence.

The street names voiced in Highways and Byways are by no means the sum total of Luton’s thoroughfares that can lay claim to a brush with the past, but should be sufficient to encourage the reader to be more aware of our hidden historical heritage and discover further examples.

No Comments

Add a comment about this page